Sequences

By Kaz Zhou, January 2021. Revised April 2021

In programming, we often need to write fast algorithms that use enumerable collections. Currently we use the list datatype to represent enumerable collections. There are some crucial limitations of lists though.

A great application of SML's modules system is the sequence signature. The implementation of sequences (which is specific to 15150) allows for parallelism and accessing any element in O(1) time; it also comes with some helpful functions.

Similar to our notation for lists, our notation for sequences looks like <x_1, x_2, x_3, ..., x_n>.

Sequences vs. Lists

Here are some advantages / disadvantages of sequences and lists. Considering sequences and lists purely from an algorithm-writing perspective, the only con of sequences is the slow cons operation.

| Sequences | Lists | |

|---|---|---|

| Accessing element i | O(1) | O(i) |

| Parallelism | ✅ | ❌ |

| Pattern matching | ❌ | ✅ |

| cons operation | O(n) work | O(1) work |

| Writing proofs | Difficult | Relatively easy |

Important sequence functions

Some frequently used sequence functions are nth, tabulate, map, filter, and reduce. For a comprehensive documentation of the sequence library, see http://www.cs.cmu.edu/~15150/resources/libraries/sequence.pdf. The following section will define each of the functions, give examples of their usage, and analyze their work and span.

Seq.nth

The function Seq.nth allows for extracting any element from a sequence in O(1) work and span. This is a significant advantage over lists, which could take up to O(n) work and span, in the case of finding the last element of the list. Seq.nth has type 'a seq -> int -> 'a seq.

An example: Let's say the sequence S is bound to the value <0, 1, 2>, which has type int seq. Then,

Seq.nth S 0evaluates to0Seq.nth S 2evaluates to2Seq.nth S 5raises an exceptionRange, which occurs when the index is too large or small.

Seq.tabulate

This is a very common tool for constructing a sequence. The type of Seq.tabulate is (int -> 'a) -> int -> 'a seq. The first argument is a function which maps an index to a value, and the second argument is an integer specifying the length of the sequence. In general:

Seq.tabulate f n ==> <f 0, f 1, f 2, ..., f (n-1)>

As a concrete example:

Seq.tabulate (fn i => i) 5 ==> <0, 1, 2, 3, 4>

Let's try writing a function that reverses a sequence. For example,

reverse <0, 1, 2, 3, 4> ==> <4, 3, 2, 1, 0>

This function reverse would have type 'a seq -> 'a seq. In the above example, we have a sequence of length 5. The element at index 0 moves to index 4, the element at index 1 moves to index 3, ..., the element at index 4 moves to index 0. Generally, if the sequence has length n, the element at index i should move to n - i - 1. It's pretty easy to make off-by-one errors here, so be careful and test sequence functions thoroughly! The implementation of reverse is as follows:

fun reverse S =

let

val n = Seq.length S

in

Seq.tabulate (fn i => Seq.nth S (n-i-1)) n

end

It's also possible to write functions that deal with nested sequences. Let's write a function multtable : int -> int seq seq that, when given a positive integer n, makes an n by n multiplication table. For example,

multtable 5 ==>

<<0,0,0,0,0>,

<0,1,2,3,4>,

<0,2,4,6,8>,

<0,3,6,9,12>,

<0,4,8,12,16>>

This time, the function that we're tabulating with needs to output a sequence, like <0,2,4,6,8>.

Here is the implementation:

fun multtable n =

Seq.tabulate (fn i =>

Seq.tabulate (fn j => i*j) n) n

Let's analyze the work of multtable. The function (fn i => Seq.tabulate (fn j => i*j) n) has O(n) work. This is since the function evaluates i*j (for different values of j) n times. The function is called n times (from the outer tabulate). Therefore, the total work of this function is O(n^2).

For the span analysis, note that the function (fn i => Seq.tabulate (fn j => i*j) n) has O(1) span, because i*j is evaluated in parallel for all the different values of j. Then, the entire function has O(1) span because the function (fn i => Seq.tabulate (fn j => i*j) n) is called all in parallel.

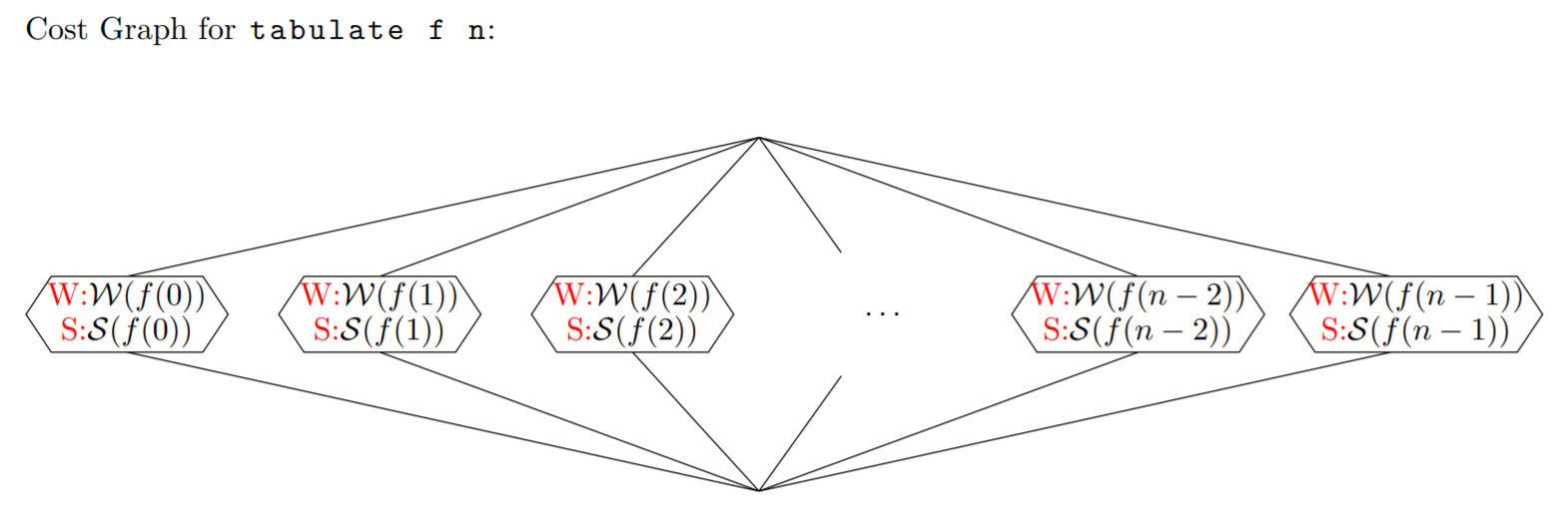

In general, the cost graph for Seq.tabulate looks like this.

The work of Seq.tabulate f S is the sum of all costs in the graph above. The span is the maximum cost of any one of the branches, because the function is called on 0, 1, ..., n-1 in parallel.

Seq.map

Seq.map is similar to List.map. The type of Seq.map is ('a -> 'b) -> 'a seq -> 'b seq. Given a function f : 'a -> 'b and a sequence <x_1, x_2, x_3, ..., x_n> : 'a seq, we have:

Seq.map f <x_1, x_2, x_3, ..., x_n> = <f x_1, f x_2, f x_3, ..., f x_n>

The work of evaluating the above expression is (work of doing f x_1) + (work of doing f x_2) + ... + (work of doing f x_n). The calls f x_1, f x_2, f x_3, ..., f x_n are all done in parallel. So, the span is the max of (span of doing f x_1, span of doing f x_2, ..., span of doing f x_n).

Seq.reduce

Seq.reduce is like List.foldr, but with sequences. The type is Seq.reduce : ('a * 'a -> 'a) -> 'a -> 'a seq -> 'a. In English, Seq.reduce takes in a combining function, a base value, and a sequence to "reduce". For example, Seq.reduce g z <x_0, x_1, x_2, ..., x_n> is extensionally equivalent to g(x_0, g(x_1, g(x_2, ..., g(x_n, z)))... ). Notice that the combining function is 'a * 'a -> 'a instead of 'a * 'b -> 'b, as in List.foldr.

The neat part is, Seq.reduce also supports parallelism. In particular, when a combining function g has constant span, then Seq.reduce g z S has O(log |S|) span. We pay a slight cost: the function g must be associative, which means that g(g(a,b),c) = g(a,g(b,c)) for all a,b,c. Furthermore, z must be the identity for g, which means g(a,z) = g(z,a) = a for all a.

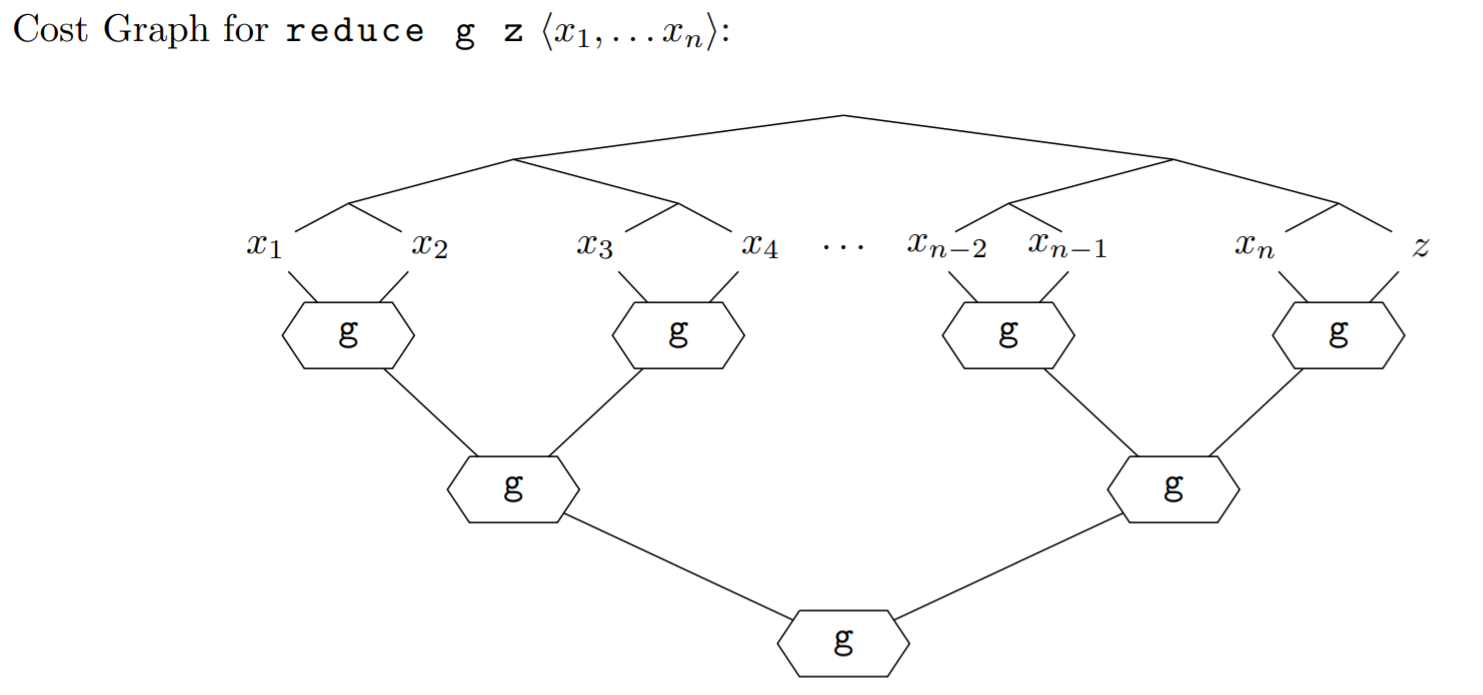

To analyze the work and span, let's consider how SML actually evaluates Seq.reduce g z S. It first calls the combining function g on each pair of elements: x_0 and x_1, x_2 and x_3, and so on. All of these calls can be made in parallel. Then, we combine the intermediate results together. At the very end, all of the elements of S will be combined together.

The work is the sum of doing all the work shown in the cost graph, while the span is the longest path through the cost graph. Therefore, for constant g, the work of Seq.reduce g z S is O(|S|), and the span is O(log |S|).

An example of using this function is finding the sum of a sequence. So, Seq.reduce (op +) 0 <1, 2, 3, 4> evaluates to 10.

Seq.filter

Again, a sequence function is analogous to a list function. Seq.filter is like List.filter. It takes in a predicate function of type 'a -> bool and a sequence of type 'a seq, and keeps elements x such that p x evaluates to true. However, Seq.filter is optimized for parallel performance. The work is O(|S|). The span is O(log |S|), which may seem surprising as the predicate function may be applied to all elements in parallel. However, it is difficult to find out the number of elements that satisfy the predicate, and thus it's not possible to find the length of the filtered sequence in O(1). The implementation details are tricky, but use a divide-and-conquer approach just like Seq.reduce.

Seq.append

Just like @, the function Seq.append : 'a seq * 'a seq -> 'a seq puts two sequences together. The work to create the appended sequence, such as in the call Seq.append (S1,S2), is O(|S1| + |S2|). To justify this, think about how Seq.append may be implemented using Seq.tabulate. The tabulating function maps indices between 0 and |S1|-1 to elements from S1, and maps indices between |S1| and |S1 + S2| - 1 to elements from S2. Additionally, the span of Seq.append is O(1) regardless of the input sequences. This makes intuitive sense because Seq.tabulate also has O(1) span, when given a constant tabulating function.

Examples of functions involving sequences

Exercise: Pascal's triangle

Our task is to write a function pascal : int -> int seq seq. Given a nonnegative integer n, pascal n evaluates to the first n+1 rows of Pascal's triangle. For example:

pascal 5 =

<<1>,

<1,1>,

<1,2,1>,

<1,3,3,1>,

<1,4,6,4,1>,

<1,5,10,10,5,1>>

Let's try to do this task without using the formula for entries of Pascal's triangle. The 0th row of Pascal's triangle is our base case. Then, we can add elements from the (n-1)th row to calculate elements in the nth row (in parallel!). This is an incremental approach: we add one row of the answer at a time.

This problem has a bit of a dynamic programming flavor, in that we should remember the previous row to help calculate new rows. One issue is that using Seq.append or Seq.cons to add a row to a sequence is expensive. However, remember the pros and cons of sequences vs. lists! Adding on a row to a list requires just O(1) work. Therefore, our approach for this problem will use both sequences and lists. The solution is below. Note that it uses the function reverse from the Seq.tabulate section of this article.

fun pascalH 0 = [Seq.singleton 1]

| pascalH n =

let

val (prev::rest) = pascalH (n-1)

fun rowmaker 0 = 1

| rowmaker i =

if i = n then 1

else Seq.nth prev i + Seq.nth prev (i-1)

val new = Seq.tabulate rowmaker (n+1)

in

new::prev::rest

end

fun pascal n = reverse (Seq.fromList (pascalH n))